Connecting Texas books and writers with those who most want to discover them

TRAVELING?

Don't miss our

Top Bookish

Destinations

Lone Star Book Reviews

by

Texas-based writer Rod Davis is the author of the novels South, America and Corina’s Way and the nonfiction American Voudou. www.rodavisauthor.com

Texas-based writer Rod Davis is the author of the novels South, America and Corina’s Way and the nonfiction American Voudou. www.rodavisauthor.com

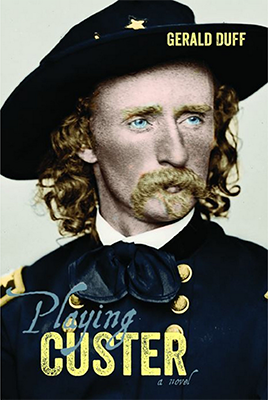

Gerald Duff is a winner of the Cohen Award for Fiction, the Philosophical Society of Texas Literary Award, and the Silver Medal for Fiction from the Independent Publishers Association. A member of the Texas Institute of Letters, he has published nineteen books. He published Home Truths: A Deep East Texas Memory with TCU Press in 2011. He resides in Lebanon, Illinois.

277 pgs., 978-0-87565-606-9, $22.95 paper

“No? What where they doing then when all that killing was going on?”

![]()

![]() LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE copyright © 2015–18 Paragraph Ranch LLC • All rights reserved • CONTACT US

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE copyright © 2015–18 Paragraph Ranch LLC • All rights reserved • CONTACT US